‘move your paddle silently through the water’

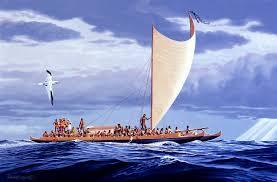

‘move your paddle silently through the water’Departing Auckland one sunny autumn day on 18 April 2010 a remarkable odyssey across the Pacific commenced as four WAKA HOURUA (double hulled voyaging canoes) sailed out of the sparkling waters of the Waitemata Harbour, their tan sailspushing these sleek 72 footwaka towards their first destination, tiny Raivavae, an Island in the Austral Group 500 miles south of Tahiti, French Polynesia about 2000 nautical miles away. It is the start of a pacific wide malaga or goodwill voyage to promote traditional navigation and culture, protection of the environment and to pay homage to the ancestors.

The vessels and their crew combine the diverse talents of a former Prime Minister ( the legendary late Sir Tom Davis- designer and builder of Te Au Tonga from Rarotonga) local designer Nick Peel, the venerable Salthouse Boatbuilders Ltd , a german philanthropist Dieter Paulmann (ONP Productions /Okeanos Foundation), master traditional sailor and carver Te Aturangi Nepia Clamp, an international crew of men and women totalling 90 from as distant lands as Finland, Sweden, Tahiti, Tuamotus, France, England, Marquesas, Moorea, Raiatea ,Tahiti Nui, Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, Australia, Vanuatu, Cook Islands, Raivavae and Aotearoa. 3 Support craft, Ranui -well known local wooden 72ft ketch, Evohe, steel, 82ft ketch and Foftein a 109 ft alloy German Frers sloop make up a fleet of 8 and a total complement of 107 people.

Together they are called Tavaru – Pacific Voyagers, a loosely knit group of voyaging societies from around the Pacific whose members are dedicated to protecting and educating their people , particularly their young, about traditional voyaging, voyaging culture and the protection of the environment and the creatures of the sea.

The uninitiated know little of the adventures to befall them. They will meet Heads of State, receive the generosity of whole islands, be treated like royalty wherever they visit, be feted and honoured with thousand year old blessings from sacred waters, be invited on to ancient marae, endure storms, limited rations, wet bunks, tinned corned beef for breakfast lunch and dinner and see and feel the might, yet embrace, of Moana Nui A Kiwa, the great Pacific Ocean over which their ancestors travelled so long ago to discover new lands.

Each crew member has passed a Coastguard day skippers course as a minimum plus a 6 month training programme from the voyagers base at Devonport Auckland. Put in place by Rob Hewitt, ex navy and a diver well known for his surviving several days at sea in his wetsuit, they must swim 500m , tread water for 30 minutes, learn knots, boat handling, sail repair, maintenance, safety procedures including man overboard and other protocols are strictly adhered to. Captains have a minimum of Ocean Yachtmasters tickets or equivalent and all carry a back up GPS just in case there are doubts over the traditional navigator’s positions. Support craft are given each waka’s position twice a day by VHF. If the flotilla become separated beyond VHF reception (often only 15 miles) Iridium phones and email are resorted to.

WAKA HOURUA

The waka (“vaka” – Cook Islands, “va’a “, Tipairua, –Tahiti, “Vaatele” –Samoa, “Ndrua” –Fiji, “Kalia” – Tonga) are an interesting mix of 2000 year old design and 21stl century equipment, still steered by a gigantic wooden “Hoi” or steering paddle, but hulls made from Foam and E glass, on a mould – vacuum bagged, laminated kwila “kiato” or deck beams (12) lashed using traditional method but with Dyneema Braid to the hulls, , on deck cabin (”whare”) made from bamboo, decking 2 inch kwila planks, , stainless steel centreboards, 2 four KW electric propulsion units custom designed in Germany powered by 8, 130 watt solar panels through 12 Lithium –ion gel cell batteries, 18 berths , 9 in each hull, all water stored in jerry cans and one onboard head(toilet)located on deck forward of the whare, rigging dyneema braided rope, spars Oregon, one back up handheld GPS, 2 Iridium satellite phones with email capability and a VHF radio.

The waka were built to strict survey requirements set out by Germanisher Lloyd. Even the Kiato (cross beams) were load tested (30 tonne break load) and hulls were core sampled after completion.

Specifications:

Design; Traditional Tuamotan “Tipairua” redrawn by Nick Peel of Auckland on dimensions from Te Au O Tonga (Sir Tom Davis) and Te Aturangi Nepia Clamp

LOA 72FT

BEAM 21 FT

DRAFT 3 FT

AUXILIARY: 1 KW Solar panels twin 4 kw electric propulsion units.

Hull construction Foam sandwich E GLASS to Hi Modulus Specs, pre cut and approved by Germanisher Lloyd

Decks Kwila Timber

Displacement; 13 tonnes

Rig 1: Voyaging rig – ketch Bermudan with jib and genoa with Dyneema standing rigging,

Rig 2: Traditional Marquesan crab claw with dyneema standing rigging

Sail: North Sails- Tan Dacron, plus traditional Pandanus woven mat sails.

Berths: 18

Instrumentation/Navigation –nil

Built and surveyed to Germanisher Loyd approval

Registered Cook Islands

Project Manager: Te Aturangi Nepia Clamp

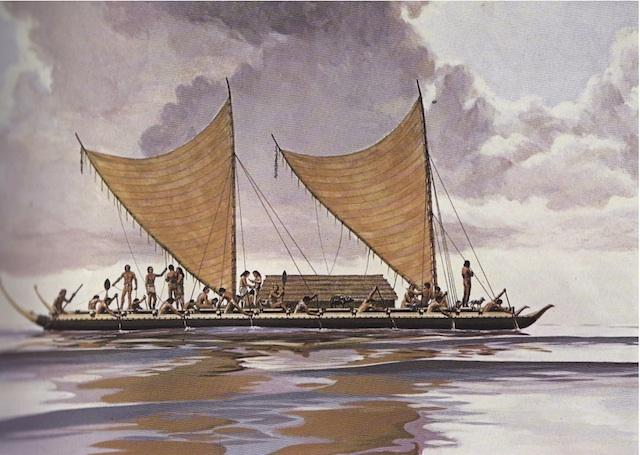

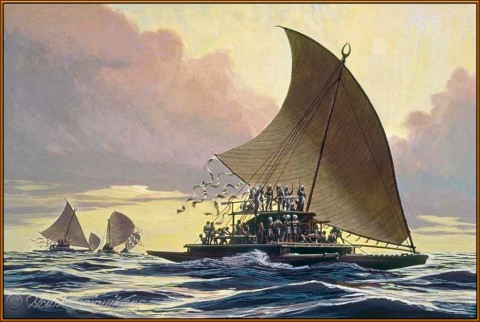

Waka by Herb Kawainui Kane

Waka by Herb Kawainui Kane

The Crews and Waka

Fiji – Uto Ni Yalo – (“heart of spirit”) Skipper Jonathan Smith

Navigator: Colin Philip

Samoa / Vanuatu/Tonga – Hine Moana (“woman of the ocean”) Skipper/Navigator Marc Gondard

Aotearoa – Te Matau o Maui (“the jawbone of Maui”)

ONP Representative; Magnus Danbolt

Navigator: Hoturoa Kerr/ Tahi Pariente

Cook Islands – MaruMaru Atua (“under the protection of God”)

Skipper : Duncan Morrison

Navigator: Tetini Pekepo, Tua Pittman, Ian Karika, Peia Patai

Tahiti – Fafaaite- (“reconciliation between man and his environment”)

Skipper/Navigator : Teva Plichart

Traditional navigation

Many wonder what the fuss about traditional navigation is. Put simply it is a method of navigation that does not use any instruments. Modern sailors have GPS, Radar, Auto Pilots, older sailors sextants, compass, tables etc. These instruments can fail. A competent and aware skipper uses the traditional techniques regularly, involving as they do an intense study of the surrounding environment- sea, sky, birds, sun and moon.

Fijian Ndrua by Herb Kawainui Kane

Fijian Ndrua by Herb Kawainui KaneMore importantly from a cultural perspective use of traditional navigation helps dispel the myth that our ancestors accidentally arrived or were simply “blown here”. This myth was promulgated since Europeans first encountered Polynesian craft and arrogantly wondered how such “noble savages” navigated without any instruments across the 1.5 million square miles of Pacific Ocean against the prevailing winds mostly before the birth of Christ and when European voyaging was non existent. This accidental voyaging theory was later supported by amateur anthropologists like Andrew Sharp and, to some extent Thor Hyderahl and over dramatized by CF Goldie in his controversial oil painting of a maori waka approaching land in a storm.

In fact the navigator in ancient island societies was the highest ranking “tohunga” or expert. He (rarely a “she”) could get the people off the island or back to the island before and after a hurricane, war or famine. Navigators were chosen young (5-10 years old) and had to learn all the stars in the star compass, their rising and setting angles off by heart plus all the other information before they were allowed to actually navigate themselves. Nothing was written. The wind, the waves and the stars were their friends. They could read the water for signs like swells, currents, cross swells, reflected waves, recognize birds and know how far they were from land, predict the weather with uncanny accuracy and they could gauge their position from the sun, stars and moon. All this was done without recording a single word. Navigators might stay awake for the duration of the voyage because if they fell asleep and the weather changed they might become disorientated. It was hard work.

Captain Cook knew, once he had observed Tupaia on board Endeavour pointing out all the known islands of the Pacific and their direction from Tahiti, that the traditional navigators were expert sailors. Indeed he witnessed the speed of the waka he encountered noting “they sailed at speeds 3 times that of Endeavour with ease”.

Of course a western style “Master Mariner” also has to undergo a similarly rigorous training involving years of sailing and learning.

Modern “way finding” saw its renaissance in 1976 when a group of Hawaians led by Ben Finney, an anthropologist professor at Bishop University and Herb Kawainui Kane a Hawaiian artist and canoe designer formed a society, built Hokule’a and sailed her from Hawaii to Tahiti without any instruments at all. David Lewis a NZ doctor and writer of many books on the subject was part of the crew also. The late Mau Paialug the so called “Last Navigator” from Satalwal Island, Micronesia was recruited to help and he trained the Hawaiians, New Zealanders, Cook Islanders in his nearly lost art. He had realised that on his island too the ancient art and such a vital part of his culture was fast dying out. (Sadly he died in July this year of complications from Diabetes- however his legacy lives on in the newly inducted palu ( graduated navigators of the Waireng School in Micronesia).

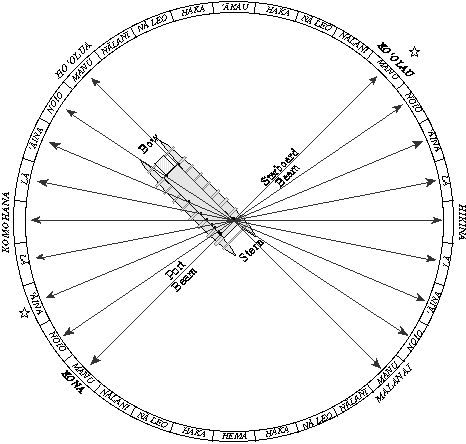

Stars, waves, wind, swells, birds, clouds, whales, underwater incandescence (“te lapa”) even seaweed floating are all used by the traditional navigator. The waka has on board reference points marked around its hull so that if a certain star is sighted it can be followed by keeping it on that mark on the waka. (see diagram 1 below) .

The navigator has often over a hundred different stars in his memory with their rising and setting positions. He imagines his canoe as the centre around which all the stars are moving. He knows this is not how the universe works but it is a method of navigating. Often a story is memorised which depicts a voyage and the various rising and setting stars that will be encountered along the way. Hands, fingers are used to calculate the distance from the star or heavenly body to the horizon to determine latitude, although concepts such as latitude and longitude are not really part of traditional navigation.

Course strategy

Herb Kawainui Kane

Herb Kawainui Kane

Before a voyage by sail begins, the way finder designs an ideal course for reaching the destination from the starting point, given the capabilities of the vessel and the winds, currents, and weather conditions anticipated along the way. The course should represent the most efficient way of getting to the destination, given all the factors listed above. The way finder must also choose the right time to go (when the wind and weather conditions are the most favorable), taking into account the timing of the return voyage as well.

Herb Kawainui Kane

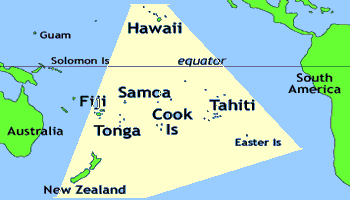

Herb Kawainui Kane The “Polynesian triangle” Hawaii Rapanui, Aotearoa

The “Polynesian triangle” Hawaii Rapanui, Aotearoa

Navigation routes of the Polynesian

Navigation routes of the Polynesian

Diagram 1

Diagram 1The waka has on board reference points marked around its hull so that if a certain star is sighted it can be followed by keeping it on that mark on the waka. (see diagram 1 above)

“My Father taught me that the sea is full of signs.

“My Father taught me that the sea is full of signs.Let’s say we leave on a voyage at sunset. At

midnight the navigator listens for the chirping birds.

You and I don’t hear them-we can’t hear them.

Only the navigator can hear them.” (Mau Piailug)

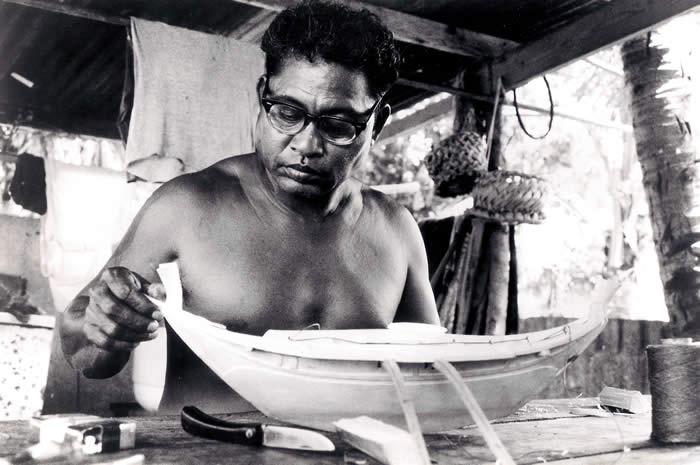

Mau Pialug from Satalawal Atoll, Micronesia “the Last Navigator”

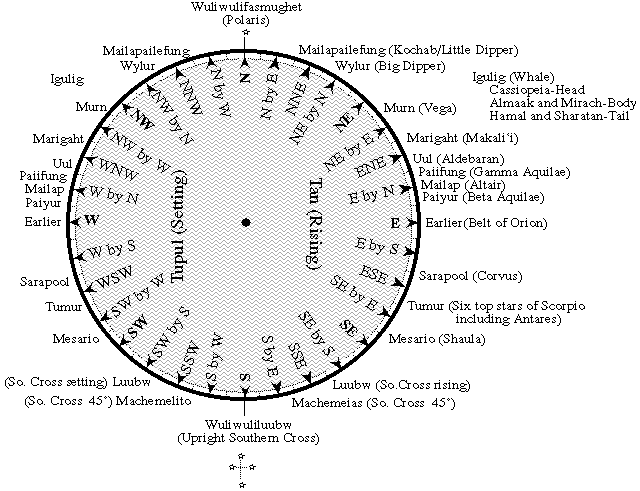

Diagram 2 The star compass showing rising and setting angles of important stars (Referred to as “Mau’s star compass” after the legendary late Mau Paialug from Satalwal Island , Micronesia, who taught 20th Century Hawaiians the ancient way finding methods culminating in the first non instrument voyage by Hokule’a from Hawaii to Tahiti in 1976)

Diagram 2

Diagram 2 Mau Piailug draws the star compass on the beach

Mau Piailug draws the star compass on the beach

The Voyages

Auckland to Raivavae (2000 n.m heading 080 T)

Marumaru Atua skippered by Duncan Morrison but navigated traditionally by Tetini, (“Ti’), Tua Pittman, Ian Karika and Peia Patai were chosen to lead the fleet. Between them they have the most experience having sailed Te Au O Tonga around the Pacific many times. (Tua and Peia also had experience with the Hawaians who lead the modern renaissance of traditional voyaging with Hokule’a). The strategy involved sailing east along the latitude of Auckland or below to take advantage of the expected westerly winds then turn left when the South East winds would enable the waka to sail directly to Raivavae .The rising and setting sun, the Southern Cross and Venus setting were the main celestial objects used.

A trip to Auckland’s Stardome Observatory prior to departure assisted all the crew to orient themselves with the night sky they would encounter at different latitudes and to identify meridian pairs of stars (helpful in establishing latitude). The waka can achieve sailing angles of about 75 degrees off the true wind, less than mono hull racing type yachts. However on a reach their speed is impressive with a maximum recorded on GPS of 19 knots. Quite a handful when steering is by a giant Hoi or paddle (about 9 inches diameter laminated Oregon) off the stern. Often it might take 3 people to handle the Hoi in a pitching sea.

Generally favourable winds were encountered and only one storm with squalls in excess of 50 knots. This was testing for the sailors with a week of easterly storm force conditions, squally with 6 metre swells. Then a squash zone between a semi stationary high and a low in the tropics kept a strong easterly flow over the fleet.

The waka handled these conditions well with their voyaging rigs (Bermuda style main and mizzen) . Conditions aboard were damp to say the least and many a hot soup and cups of tea were needed.

Excerpt from daily report 27 th April

Day 9 270410

ANZAC day: The heavier weather from south east doesn’t bring down the crews moral. Instead the amping, yeehaaing increases and everyone gets their glow on. There are no worried faces when the vaka surfs down a wave and buries her bow through on coming waves. It is a constant rhythm if you are down below in the hull. It sounds like thunder and the hulls shudder on impact. You can hear the water hit the top of the hull and cascade down like a waterfall. It sounds surreal ………….At 0400 the wind increased to gale force. We took another reef and are running under 2nd reef on mizzen and main and staysail. We are still doing 10kn and 15-17kn down the waves. Big swell and spray whipping our faces in the wind. The canoe is being thrown around and a wave breaking over the deck took Tiaki, the youngster onboard, with it all the way to the guard rail. Luckily he is unharmed. Another day of voyaging!

See above attached report from Te Matau a maui;

At about longitude 152 w the fleet turned to Port much to the relief of all as this meant warmer weather and maybe the trade winds. Te Matau ONP representative suggested after the wind died that the fleet go under tow, which did not receive too much support but eventually they succumbed and reluctantly took a tow line for a couple of days towing through the dead wind zone, to finally arrive in Raivavae some 18 days after leaving, no injuries, no serious damage and some new experiences for the ones who had never completed an ocean passage.

Meantime Faafaite skippered by ex Americas Cup sailor Teva Plichart sets sail from Papeete to meet with the voyagers at Raivavae. Aboard are a crack crew of men and women from Tuamotus, Tahiti, Moorea and Raiatea plus Te Atu Rangi from Cook Islands. Its a warm get together when the fleet meet in tiny Raivavae.

The welcome at Raivavae is hard to believe. Dancing, singing feasting goes on for days. All are presented with gifts of local model canoes, food, poi, and other mementos of our stay there. The tables are laden with local delicacies. The beautiful dancing girls beckon and tease the sailors to dance. The leaving ceremony is equally impressive yet sad as one of Raivavae’s sons Tetiawa left with Faafaite, the Tahitian waka. Known as one of the homes of legendary navigator Iro or Ironui, Raivavae has had a close association with traditional navigation. Even while the fleet awaited appropriate winds to leave relaxing in the lagoon, locals showered them with banana paw paw, fish, taro and yam.

Fijians dance at Raivavae

Fijians dance at RaivavaeRaivavae to Moorea

ONP representative Magnus Danbolt recommends towing to Moorea in order that the schedule of ceremonies yet to come is kept.

Setting off into a dying Nor East the waka take the towline reluctantly. Later an easterly springs up and several waka let go the lines and let these ocean canoes stretch their legs. “Full and by” is the best sailing angle for these craft and they will easily reach speeds of 9 knots in a 15 knot breeze on this angle.

First port of call in Moorea is Haapiti on the south west coast, a great surfing break and the surfers amid the crew led by ex World champion kite surfer Marc Gondard, skipper of Hine Moana, take advantage of this left hand reef break. Faafaite and Ranui celebrate the catching of a large bull Mahi Mahi.

But local Mooreans don’t want to be outdone by their Ravavae cousins and so put on an equally spiritual homecoming in stunning Opunho Harbour . Every sailor is blessed with the water from the sacred spring of the Octopus’s well just outside the 8 sided church giving the recipient wisdom knowledge and bravery in the face of adversity. Then to a feast in the whare which goes on all day, a bus tour showing the sacred sights

Faafaite in light airs at Moorea

Faafaite in light airs at Moorea

Dancing girls Moorea

Dancing girls Moorea

Blessing from the well of the octopus (The Fe’e)

Blessing from the well of the octopus (The Fe’e)

Faafaite crew perform a haka on board as they sail past Ranui after releasing dreaded towline en route to Moorea

Faafaite crew perform a haka on board as they sail past Ranui after releasing dreaded towline en route to Moorea

Uto Ni Yalo against the dramatic landscape of Moorea

Uto Ni Yalo against the dramatic landscape of Moorea

Moorea to Tahiti Nui

Dance celebration at Papeete

Dance celebration at Papeete

Sacred marae Taputapuatea the place where a millennia of voyagers learned the arts, left and arrived for foreign islands.

Sacred marae Taputapuatea the place where a millennia of voyagers learned the arts, left and arrived for foreign islands.All waka sail slowly in light airs to a hero’s welcome in Papeete led by local sailors on FAAFAITE the waka moor up on the beachfront to a throng of expectant locals, drums beating and a brilliant welcome ceremony comprising oratory, dancing, presentations both to and from the waka sailors. Then began a full tour of Tahiti including the magical marae in the hills known as Faare Hape , a series of waterfalls, pools, ancient statues and a marae that dates back centuries where spiritual healing and learning has occurred for hundreds of years. All the crew sleep the night partying and feasting on the generosity of the Tahitian hosts of Tavaru.

The canoes are then re provisioned in readiness for the culturally important trip to Raiatea, legendary source of so many of the canoe that voyaged to Rarotonga, Hawaii, Aotearoa and beyond. There the ancient marae Taputapuatea awaits their arrival.

Tahiti Nui to Raiatea

It is a tradition that good luck will follow if a rainbow is seen and dolphins guide the waka into this sacred island and it certainly happened. In fact Faafaite the Tahitian waka with French Tahitian ex Americas Cup and ocean racing sailor Teva Plichart skippering leads the fleet into Raiatea in a Rainbow, having not long before been escorted by not only dolphins but whales.

Each crewmember is taken by local waka inside the lagoon to receive the welcome standing in knee deep water and then a more formal welcome to Taputapuatea, the ancient marae where navigators from old Tahiti were trained and which is the repository of many many sacred mauri stones deposited by voyagers for hundreds of years from their own islands. The crew pay homage to their ancestors in the time honoured way by laying sacred Mauri stones on the marae.

Entering the traditional Passe Tevamoa (Hokulea once entered the wrong pass – thought to bring bad luck) the fleet anchored and with much trepidation walked to the sacred place of their ancestors, encircled by the rope of those few chosen to be invited to this marae. There the local chief and relative of the King of Raiatea welcomed the crews who in turn presented a magnificent carving by Te Aturangi carried into the marae by Jamaal Pakoti, one of the youngest yet most enthusiastic members of the Cook Islands crew.

From there the waka sailed to yet another welcome at Uturoa the main township, taking the passage through the inner lagoon arriving to a fanfare with fire brigade hoses and more partying. Raiateans showed their party spirit by hosting the crews to an all night party on the wharf promenade.

From there the fleet proceed to a small motu named TAHUNOAE (or Mirimiri) where a day or two was spent relaxing with locals, surfing the famous point break, celebrating Teva’s birthday and finally attending a sad farewell ceremony where gifts of voyaging food poe ana (sweet taro and sugarcane pressed into a bamboo tube) and mauri stones were presented.

Leroy gets some air on a right hander at Mirimiri

Leroy gets some air on a right hander at MirimiriThe fleet then left the passage Rautoanu for the 540 mile voyage to Rarotonga where the fleet would divide with Tahiti canoe returning and Cook Island canoe staying in their home island.

Raiatea to Rarotonga

”Along the sacred pathway of our ancestors”

Marumaru on her way home crab claw rig goosewinged with headsail

Marumaru on her way home crab claw rig goosewinged with headsail

A gentle breeze built to a perfect easterly and with Tua Pittman and Peia Patai navigating the lead canoe Marumaru Atua we were directed to steer just to the right of the southerly swell. Crab Claw rigs are set and the canoes fly at 9-12 kn. Faafaite catches a 120 kg MARLIN on the way which they distribute through the fleet with just one mishap when Foftein collides with Hine Moana whilst transferring the fish. At the end we arrive a little too late for the celebrations to start that day so we drift in the night to anchor off the harbor and then sail the next day to Avana past the waiting crowds in Avarua sitting on the shore or waiting impatiently at Trader Jacks bar. It seems the whole of Rarotonga will be there at the welcoming at the small harbor where all voyaging canoes have departed or arrived over the centuries. Ably organized by Eva Nepia Clamp the ceremony here is very emotional. First in the pass is Maru Maru Atua whose crew is fully decked out in traditional costume. Ashore the kaumatua welcomes them dressed from head to tow his headdress containing red tevake bird feathers, black pearls and mother of pearl shells. Beside him a smoke fire is laid and each sailor cleanses himself in the smoke as they near the formal welcome. The Prime Minister, the former Prime Minister and VIP’S gather in a giant tent awaiting the speeches dances and inevitable feasting. There’s hardly a dry eye in the place. It was after all the Cook Islanders ,in particular Te Aturangi and Ian Karika who kicked this whole idea off not even 2 years ago and now they have sailed into Avana Harbour with one of the biggest fleets of waka (vaka) in living memory. Such is the status of traditional voyaging here that the Prime Minister Jim Marurai invites the whole fleet to a luncheon in our honour at his residence. Exquisite food and short speeches make for a great day.

Mauri stones are laid near Avana in another Taputapuatea where generations have previously.

With a sad heart Faafaite sails back to Tahiti and the reduced fleet of 3 waka sail out to Samoa some 800 miles north East. We are farewelled by MaruMaru Atua who sails out with us as we leave Avatiu harbor. Manuia ! Rarotonga!

Rarotonga to Samoa

Light winds prevailed in this leg. Uto Ni Yalo displayed excellent sailing skills with her gennaker and spent the days jibing on the lifts and sailing apparent wind angles effectively. In one jibe she puts 40 miles on the other two (one of whom doesn’t have a gennaker and the other flies hers sideways)

Te Matau takes a tow for scientific purposes and miraculously appears ahead of Uto Ni Yalo who refuses to tow. The fleet bunch up and split from the support craft for the rendezvous at the narrow pass at Sinalei on the south east coast.

The waka beach at Sinalei resort where about a year before the Tsunami hit with such devastatation and the tragic loss of owner Joe Annandale’s wife and many others. There another huge welcome awaits us with a bullock and pig on the spit, cold beer on tap , the Head of State to greet us and a dance group including Miss Samoa to entertain plus a great local band.

Samoan welcome at Sinalei resort, site of tsunami tragedy 2009

Samoan welcome at Sinalei resort, site of tsunami tragedy 2009 Waka on the beach at Sinalei

Waka on the beach at SinaleiSamoa to Tonga

180 miles, this the final leg with more than one waka. It’s a quick sail with nice breezes. The crews meet off a motu, see some kite surfing and relax while ashore more preparations are underway for what will be the penultimate welcome ceremony.

Tongan Beach Resort is the venue and kava flows, feasting goes on all night and nobody manages to lift the round stone on the bar, except one very large and strong Tongan expert.

Tonga to Fiji

Light easterly winds predominate this passage with Evohe Ranui and just the last, but fastest waka, Uto Ni Yalo. Passing through the Bligh Passage and the Lau group we strike fish, mahi mahi and tuna. False killer whales and good fishing on this leg interspersed with some motor sailing enable the waka to reach Suva Harbour Fiji for a hero’s welcome on the Saturday afternoon. The deputy Prime Minister gives a congratulatory speech and headlines and front 3 pages of the Fiji times are devoted to their returning sailing heroes.

Conclusion

What was learned?

‘If you don’t know where you came from you will never know where you are going”

This was a voyage to pay respect to the ancestors. It is the continuation of the renaissance of a culture nearly destroyed by a succession of external pressures.

As such the sailing was just a small part of the cultural importance of Tavaru. It was more about re establishing relationships with the cousins of the Pacific Ocean“Moana nui a kiwa”

The homecoming and goodbyes on land involved the whole community who in turn recalled old ways, let young people see the preparation of traditional food, dancing, singing, the protocols involved in ensuring no tabu was broken, that good luck would follow the sailors.

The passing of legendary Mau Piailug has meant a refocus on the old skills of traditional navigating is needed. Learning from the stars, wind, swell, birds will mean the art of the way finder will not die.

For the sailors they became brothers and sisters of the sea and touched their ancestors offering the respect they deserved for having travelled so many miles centuries ago. They did not have to conquer the seas but the stars wind and waves became their friends, at one with nature.

The bringing together of the people to show their pride in not only the sailors, the waka but also their historic and modern day lives was a privilege to witness.

The waka themselves proved safe and trouble free. The crews developed obvious pride in their skills and they in turn will be able to impart their newly learned knowledge to others.

There is a planned trip to Hawaii next year possibly involving seven waka and a documentary and the lessons learned in this Malaga will hopefully be adopted if this plan comes to fruition. The use of AIS or GPS tracking devices will no doubt assist the support vessels but also enable the traditional navigators to do their job without overhearing the Captains record the GPS positions over VHF.

Preservation of the environment; It is hoped the publicity around the voyage did not miss the real philosophy behind the reunion voyage and that is that the ocean is in peril and must not be taken for granted as acidification of the water destroys coral , pollution endangers fish, overfishing exploits nature’s bounty and underwater noise affects dolphin and whale and many other species.

In Memoriam; Mau Piailug “the Last Navigator”

Born: Pius Piailug 1932

Weiso, Satawal, Yap, Federated States of Micronesia Died July 12, 2010 (aged 78)

Satawal, Yap, Federated States of Micronesia Cause of death Complications of diabetes Nationality Micronesian Other names Mau, Papa Mau Ethnicity Satawalese Education Weriyeng school of navigation Occupation Navigator, canoe builder, teacher (kumu) Years active 1948–2007 Known for Wayfinding, Polynesian navigation, Hawaiian Renaissance Influenced by Raangipi (grandfather), Angora (uncle) Influenced Nainoa Thompson Spouse Nemwaeito (alt. sp. Nemoito) Children 16 Parents Orranipui (father) Relatives Urupoa (brother) Awards Special fellowship, East-West Center (1976)

Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters, UH (1987)

Robert J. Pfeiffer Medal (2008)